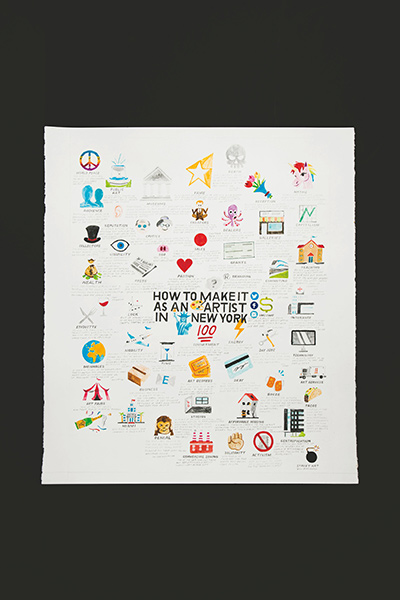

How to make it as an artist in New York

To survive as an artist takes a lot but it’s not impossible. Here’s how some of the city’s emerging artists survive

by Noah Davis

HESTER SIMPSON shares her Long Island City studio to save on rent.

In 1989, Hester Simpson found a studio on the top floor of an old factory building in Long Island City. During the past two and a half decades, she’s seen new residential buildings spring up on the waterfront, blocking her view of Manhattan, but she hasn’t left.

She recently started sharing her $544-a-month space with an architect who comes into the studio at night or on the weekends when Simpson is at home in Manhattan with her husband, a physician. She took on a subtenant after she lost a part-time job as an evaluator for the Ricco Maresca Gallery.

To supplement her income, Simpson has worked in the education department at PS1 and with mentally and physically disabled people through an agency called Healing Arts Initiative. She also has taught at Queens College. Ricco Maresca also represents the small, irregular geometric works she creates by layering dozens of coats of colorful acrylic paint on a 12- by 12-inch base. A New York Times review called the paintings “mesmerizing schematic canvases, polished and sophisticated,” and Ricco Maresca sells them for $4,000.

Although Simpson says she’s had some success with sales, and billionaire art collector William Louis-Dreyfus bought several of her pieces for $4,000 each, she hasn’t had a show since 2012, and her sales are down. She remains hopeful. “My work changed, and it has taken me time to build up a new body of work,” she said. “Early next month I will have several new pieces photographed for my website.”

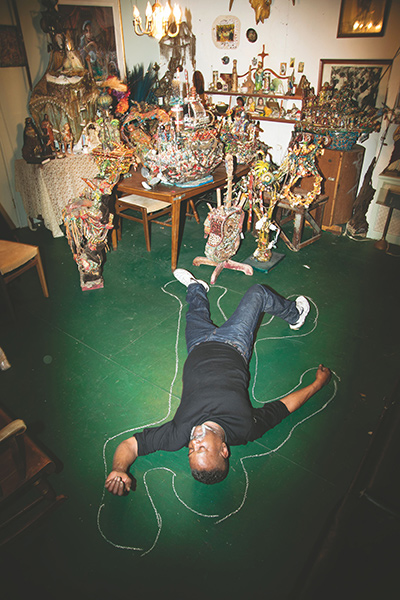

Deshawn Dumas said when he took the desires of the market into account, his financial fortunes improved. Photo: Buck Ennis

It took Deshawn Dumas a decade to make a single significant sale. In 2015, a gallery representing the now-32-year-old visual artist sold three of his bold, colorful abstract paintings that feature quotes from Enlightenment thinkers.

Peggy Cooper Cafritz, an influential collector and former president of the D.C. Board of Education, purchased one called Till the summer in the city (Get Free).

Dumas netted about $25,000 for the works. He estimates that he broke even after accounting for labor and materials, but he feels his career is gaining momentum. “This is the first time where I have a market, sort of,” he said over beer in the apartment in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, that doubles as his studio.

Illustration by William Powhida. Photo by Buck Ennis.

For the first time, he started to take the desires of the market into account when creating his works. “I had to make an adjustment between my idealism and the reality of the thing I was producing,” he said. “I have to navigate that difference between me and the audience, the people, the discourse and the market.”

Although he wasn’t accepted to that show, the paintings caught the eye of gallerist Ethan Cohen, who focuses on emerging artists and was an early patron of Chinese artist Ai Weiwei. Cohen put one of Dumas’ works into another exhibition, and brought three of his paintings, including Till the summer, to Context in Miami, a show for emerging artists that runs concurrently with Art Basel.

All three of the 80- by 48-inch pieces sold to people whom Cohen considers “important collectors.” Cohen also bought four 24- by 18-inch works directly from Dumas. “I didn’t start seeing rewards until I started thinking about the market in relation to the academic discourse on art,” said Dumas, a recent graduate of Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute, where he earned a dual master’s degree in fine arts and the history of art and design.

Art is a cornerstone of moneyed society in New York, with pieces regularly selling for millions of dollars. But most artists rarely see any of this bounty, making it harder for them to afford to live and work here. There is, however, a way to make it. The key for many artists is to think as much about the market as the art.

That’s what Dumas is trying to do as he grapples with the reality that today’s art world is increasingly market-driven: A few well-known artists create specific genres of paintings (or have their assistants produce the work), and the galleries that sell those pieces earn the vast majority of the money.

Almost everyone else loses.

“The attractiveness of the idea of being an ‘artists’ artist’ who, while just scraping by financially, steadily produces work that is respected mostly or only by his/her peers, has almost disappeared,” longtime Newsweek critic Peter Plagens said. “Nowadays, it’s more stardom or bust.”

HANGING ON: Retired cop Kevin Sampson works in a window factory when he’s not in his Newark studio. Photo by Buck Ennis.

Dumas hopes to make $60,000 to $70,000 a year, and said that’s an attainable goal in 2017. “The goal is to make a brand that’s recognizable,” the artist said. “When you see a piece, you know it’s a Dumas. That’s something I’m interested in realizing in the next two years.”

As visual art becomes an asset class and Christie’s sells Modigliani’s 1917 Nu couché for a record $170.4 million to billionaire Chinese collector Liu Yiqian (who put the charge on his American Express black card), it can be easier to sell a painting for $1 million than for $1,000.

“The art market is all about millions of dollars that maybe two [artists] get,” said Rhonda Schaller, who, as director of the Pratt Institute’s Center for Career & Professional Development, is tasked with ensuring that the school’s graduates can survive financially after they earn a degree. Pratt now offers courses and seminars detailing ways to make money as an artist through teaching, grants and other means.

William Powhida, 39, an artist whose work comments on the schism between superstar and working-class artists, says 80% of artists are making about 20% of the money. Artists get about half the sale price for works sold in a gallery, and usually nothing from resales in the private market or at auction houses, where the sky-high prices reward earlier collectors, not the creators. The other 80% of the income, possibly more, goes to a small fraction of artists, and even they make nothing from resales.

“A little bit of activity for a lot of people puts out this carrot that there’s something commercially viable about it, but if you’re selling $20,000 of art a year, that’s not anything remotely sustainable to live on in New York City,” said Powhida.

Still, getting a piece of that 80% is what Dumas and his fellow visual artists aspire to. And for that, as Dumas discovered, it’s as much about giving the market what it wants as it is about executing an artistic vision. And what the market wants is art that comes with a star and a story. In fact, last year, United Talent Agency hired Joshua Roth, whom New York magazine called “the Ari Gold of the art world,” to launch a fine-arts division with the express purpose of finding and marketing new visual-art stars.

“There’s a movement going on with the personality of artists,” former gallery owner and consultant Andi Potamkin said. Her clients take speech and improv classes to sell themselves along with their work. Cohen cited Dumas’ ability to explain what goes into his paintings as a positive factor. He has a presence and “a convincing story,” the gallerist said. “He’s African-American, well educated, [and a] high-achieving individual who decided that art was his calling.”

Ryder Ripps, 29, could become that art-world star. Called “the consummate Internet cool kid” in a 2014 New York Times story—an epithet that has followed him in nearly every subsequent profile—he gained notoriety for “Ho,” his first solo exhibition. In the 2015 show at Postmasters Gallery in TriBeCa, he produced large paintings of distorted images from the Instagram feed of model Adrianne Ho.

Response was mixed, with some reviewers calling it a cheap stunt, and others appreciating the commentary on the rapid, transactional world of social media. The attention elevated Ripps’ profile, and he said that eight of the 12 paintings sold for about $12,000 each.

The show didn’t make Ripps rich. His main source of income is OKFocus, a creative agency he founded that has worked with companies including Nike, Red Bull and Soylent, giving him a certain level of financial freedom. Like many artists, he’s reluctant to tie the art he makes to the marketplace, worried it may corrupt the purity of his work.

“Being an artist is emotionally hard, beyond being difficult to do, especially living in New York City, where everything is so expensive,” he said as he fiddled with a camera lens in his Long Island City studio. “There’s the burden to make money from [your] art. I think that is emotionally taxing and potentially toxic to your own art.”

If Ripps, a member of Forbes’ 2016 30 Under 30 Art & Style list, wanted to make money from art, he said he’d be more middle-of-the-road and not offend the viewing public. He’d produce “candy art,” like the sculptures of Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst’s current work.

These factory-style artists represent an easier path to financial success, but Ripps is following one too, despite his assertions to the contrary. He speaks his mind as a brash, unapologetic New Yorker. He knows that the art world will put him in the category of young, white, successful male artists such as Dash Snow and Dustin Yellin. His work won’t appeal to everyone, but that’s OK. “Haters gonna hate. Ironically, that perpetuates my success. I’m like Donald Trump,” he said with a knowing smile.

Ripps said the market for his work is growing, and he is planning an October show at the Steve Turner gallery in Los Angeles. He’s also in talks with Postmasters Gallery about another solo exhibition. He has a piece in the gallery’s current show, a $40,000, solid-gold statue of Pepe the Frog, a popular Internet meme. There has been interest from collectors, although no one has purchased it yet. “It’s very expensive,” a gallery representative said.

Lucien Smith is three years younger than Ripps but is already a star. In 2013, his 10-foot-tall painting Hobbes, The Rain Man, and My Friend Barney/Under the Sycamore Tree sold for $389,000 at Phillips auction house on Park Avenue. A year later, Two Sides of the Same Coin, a work the now-26-year-old made for his 2011 Cooper Union graduate show, sold for $372,000, well over the pre-auction estimate of $66,000 to $99,000. Called an art-world wunderkind by Vogue and an “artist to watch” by gallerist David Zwirner, his pieces sold for a total of $3.7 million at auction in 2014, according to industry tracking website Artsy.

Huge money, yes, but the winners were the auction houses and the art flippers, not Smith himself. The Hobbes sellers bought it for $10,000, Bloomberg reported. Smith made enough to pay rent for a few months when he sold the painting. But the auction market for Smith’s work collapsed just as quickly as it exploded. In November 2014, his When a Man Loves a Woman didn’t draw a bid at a Phillips auction.

That’s a typical trajectory for a young artist thrust into the spotlight. “The faster you burn, the harder it can be to sustain,” said Bill Powers, founder of Half Gallery on the Upper East Side, which hosted an early show by Smith. “Everyone is so quick to pile on or declare something over. There’s a lot of hate in the art world, too.”

Still, even Smith’s brief success means that he made hundreds of thousands of dollars from original sales because the galleries that sold his paintings increased their prices, and he earned half of each sale. Prices for his original works remain high, despite the cooling of the auction market for his work. SoHo gallery owner Guy Hepner sells Smith’s paintings starting at $70,000, and Powers sold a few Smith pieces in a 2015 show. Salon 94 owner Jeanne Greenberg-Rohatyn told Bloomberg, “We can sell all the paintings he gives us.” Those works cost between $10,000 and $75,000. On March 5, Smith opened a solo show at Moran Bondaroff gallery in Los Angeles.

Most artists will never see a $10,000 paycheck for an individual sale. Painter Mario Naves, 54, pays his bills by teaching six classes a semester in drawing, painting and design at Hofstra University, Brooklyn College and Pratt Institute. He also writes art criticism for publications including The Wall Street Journal and The New Criterion. When he was younger, he worked in construction so he could afford to paint.

He is represented by the Elizabeth Harris Gallery, a well-respected Chelsea shop, where his abstract, geometric works sell for $3,000 to $5,000 each. He sells a few paintings a year but views any revenue that comes from his art as a bonus. He paints because he’s driven to do it. “If I looked at my expenses over the last 25 years, I’d probably faint,” he said, surrounded by works in progress on the walls of the crammed studio he splits with another artist on the top floor of a former Long Island City factory building.

Naves tells a story that’s familiar to many working artists. A friend hosts gallery tours for the wives of investment bankers and other members of the affluent set. As a favor, she brought the group to one of Naves’ shows at Elizabeth Harris. No one purchased anything.

THE 80-20 RULE: William Powhida, shown here in his studio, says 80% of artists share 20% of the market.

Afterward, they went to a show of work by American abstract expressionist painter and printmaker Joan Mitchell at one of the blue-chip galleries in Chelsea. One woman bought a painting there for $3 million, seeing it as an investment rather than something to hang on the wall. “We’re at a stage where people will spend $3 million for a painting before they spend $3,000,” Naves said. “The commercial side feels like another world.”

Dina Brodsky, 34, is the rare artist who is making a living from her art while working outside the gallery system. She has built a sustainable business using Instagram, Etsy and, when she took care of her newborn, renting out her studio on Airbnb. “I can control my own career rather than relying on a gallery,” she said. “No one cares about your work as much as you do.”

Brodsky paints detailed miniatures of nature scenes, cityscapes and animals that range from two inches high by two wide, to eight inches by eight. Her 135,000-plus Instagram followers help her boost sales. So do her low prices—about $500 for a smaller painting. “I think if it was $10,000, I would have a much harder time making sales through Instagram,” she said. “Because it’s drawings and miniatures, people are willing to spend a few hundred dollars.”

Brodsky has a gallery show about once a year, and her sale prices have risen from $150 a few years ago to $750. At her most recent show, in 2015 at Island Weiss Gallery on the Upper East Side, she sold about half the 50 paintings, representing six months of work.

The rest sold through Instagram. Her huge following is paying off in other ways, too. Uber gave her a $200 credit for posting one of her drawings with a link, and she has received between $100 and $200 from other companies for doing the same. One art supplier gave her money, along with a variety of expensive sketchbooks and pens. She gave them away to her friends. In 2015, she made about $40,000. “For me, that’s a lot of money,” she said.

If more artists follow Brodsky’s path and find their own financial success, it will hurt the galleries that most artists rely on for sales. Rising rents are already squeezing many galleries. The largest, most successful ones, like Gagosian, Gladstone and David Zwirner, own their spaces in Chelsea and will survive. Many more are leaving the neighborhood, where annual rents can run up to $150 per square foot.

Although smaller galleries are opening on the Lower East Side (there are now 125 in the area, nearly doubling from 2010 to 2015), rent accounts for a third of a gallery’s overhead, and any increases add to the already immense financial pressures on the art marketers. (Supply stores can’t compete either. New York fixture Pearl River Mart closed its SoHo department store last year after the rent jumped from $100,000 a month to $500,000.)

Galleries are also being pressured by the growing competition from art fairs, leaving them little room for new artists whose work may take time to find an audience. The European Fine Art Foundation reported that art fairs accounted for 40% of industrywide sales revenue in 2014, up from 33% the year before.

Bill Powers, the gallerist who gave Lucien Smith his first New York solo show, said even second-tier art fairs charge $8,000 to $10,000 for a booth. Factor in shipping art to the shows and flying staff there, and it’s easy to see why a gallery can’t afford to sell paintings that cost $2,000 from an emerging artist. “That’s to the detriment of collectors and art fans in general,” Powers said.

This is the confusing game played by Deshawn Dumas and other artists, young and old. “I think you can read the market,” Dumas said. His recent success is an indication that he’s at least partially correct. Even so, it’s almost impossible that he’ll win financially in the way that Koons has. “Usually it’s the auction-house records that grab the headlines, but that’s just Powerball for billionaires,” Powers said. “That has nothing to do with working artists.”

Still, working artists will continue striving to make it in New York. Despite the rising costs, the city remains the best place to make connections, find galleries to represent their work and take advantage of art-related financial opportunities. The key for an artist is to balance the desire to create with the desires of the market.

Dumas recalled one professor’s evaluation while he was a student at Pratt. She came into his studio, looked at his work, and said that she thought it would sell. “That was her [criticism],” he said. “I was like, ‘Got any names?’”

The Recent Grad

GAIL QUAGLIATA: Photographing delis doesn’t pay the rent. Photo: Buck Ennis

From Dec. 12, 2012, to Aug. 26, 2013, Gail Victoria Braddock Quagliata photographed every bodega in Manhattan, a project that earned her write-ups in The Wall Street Journal, The Village Voice and other publications, but little financial benefit. “It’s gotten me a lot of speaking engagements and opportunities to interact with community members more than arts patrons, which has been amazing and unexpected, but I don’t have a book deal, despite trying really hard,” the 2012 Pratt graduate said in the Bushwick apartment she shares with her husband, who edits television commercials, and her cat, Optimus Prime.

A framed copy of the Journal article hangs on the wall of the overflowing eight-foot-square room between the kitchen and bedroom that she uses as a studio. Quagliata, 35, usually teaches photography and filmmaking classes at afterschool programs in Brooklyn high schools to pay the bills, although she’s taking a semester off to focus on her art. She spends a couple of hours a day applying for grants. She does most of her projects digitally because she can only afford the printing costs when someone buys a photograph for $50 to $175 off her website. “If I could make $30,000 a year on prints, I would be like, I don’t need to teach,” she said.

Quagliata knows of only one person from her graduating class who makes a living as a full-time artist, and “to be fair, he runs a residency.” Still, she stays positive: “It’s only been four years. So I’m OK. People need five years to be the emerging artist, and 10 years to be the moderately established artist.”

The Adviser

William Powhida estimates he lost close to $12,000 on his art in 2015 when he compares his sales with the time and materials he invested. He holds a full-time job as artistic co-director of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design in Dumbo, which provides him with a cluttered studio space for his text-based artwork.

Working weekends, he produces roughly 15 to 20 original pieces a year, which sell for an average of $5,000. He says he generates $60,000 to $70,000 in annual revenue through sales, half of which goes to the galleries representing him: Postmasters Gallery in New York, Charlie James Gallery in Los Angeles and Gallery Poulsen in Copenhagen. Powhida sells prints of his original works, which cost $1,000 or less. In 2014, he sold 27 prints in China after a show. Powhida’s work, which satirizes the art market, was an inspiration for 9.5 Theses on Art and Class, a book by critic Ben Davis.

“I never thought I would see my work reviewed in Art in America. I never thought I would be represented by one gallery, let alone four. I never thought I would create work that would be included in a larger dialogue,” he said. “I need to make sure that I’m not trying to define my career based on a [Jeff] Koonsian figure or the superstars.” It’s an emotionally rewarding career, but sales are sporadic: “I wish I had a little more economic freedom.”

The Survivor

The second floor of the Newark apartment that Kevin Sampson, 61, shares with his 34-year-old son is crammed with the intricate, inventive sculptures created by the former Scotch Plains, N.J., cop and self-taught artist.

He’s represented by the Calvin Morris Gallery in Chelsea and sells his works for $5,000 to $20,000 apiece. Sampson says he’s lucky if he makes $10,000 a year from art. His $25,000 early-retirement pension pays the rent, and a teaching-artist position at the Rutgers University Paul Robeson Gallery pays for his food.

Rent costs Sampson $1,100 a month, which is cheaper than it could be, but the landlord—who runs a window-making shop around the corner where Sampson works when he’s hard up for cash—“protects me,” Sampson said.

He is considered the leader of a small group of older artists in Newark trying to hang on as an influx of younger artists flee the high prices of Manhattan and Brooklyn, in turn driving up rents in New Jersey’s biggest city.

“Newark is a mess,” he said. “We need new people, but I want to make sure that the artists who stayed here when nobody wanted Newark don’t get lost in the shuffle—that our legacy continues. I’m like the ringleader, raising hell.”

A version of this article appears in the March 21, 2016, print issue of Crain’s New York Business.