Hester Simpson

Mario Naves

Ricco/Maresca Gallery

Published 2012

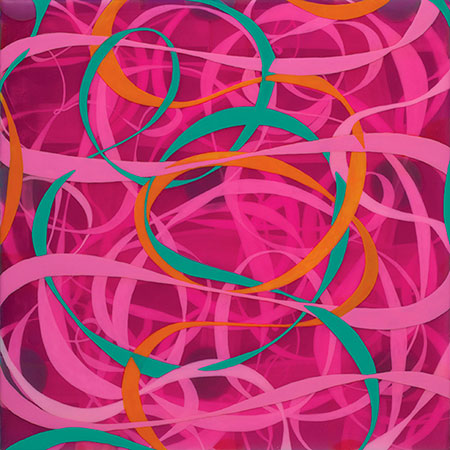

Ephemera, 2011, acrylic on wood panel, 12 x 12 in.

Simpson coaxes from acrylic paint a remarkable suppleness—remarkable because synthetic materials don’t inherently lend themselves to sumptuousness of tone and surface. Her patterned geometric shapes and calligraphic structures are luxurious in a way that seems incommensurate with the medium. The surfaces of Simpson’s paintings have a distinct tactility–a warmth and luster–that is akin to, if not flesh, then something close to it. Ask yourself this: When was the last time you longed to trace your fingertips over plastic? The paintings beg for an appreciative touch.

Through ongoing and thorough experimentation, Simpson has discovered technical means by which acrylic paint is both a sensual substance and the carrier of metaphor–of sensations that transcend the blunt physical fact of mere stuff. Big deal, right? We should expect the same from any painter worth her salt. But in an age when virtual wizardry can obscure material pleasure, Simpson’s achievement–a kind of alchemy, really–is worth elaborating upon. The pictures, though hushed in demeanor, are adamantly anti-virtual.

There is, of necessity, a prosaic side to life in the studio–stretching canvases, washing brushes, mixing pigments and allowing the requisite time for paint to gel and harden. Simpson can undoubtedly enumerate the recipes and procedures by which she creates her signature runs of pictorial incident. But if the images were little more than compendiums of expertly contrived effects, it’s unlikely they would be as absorbing. Creating fetching surfaces is vital, absolutely. But endowing them with metaphorical resonance is another thing–and no mean feat. Simpson has, with impressive consistency, proved up to the task.

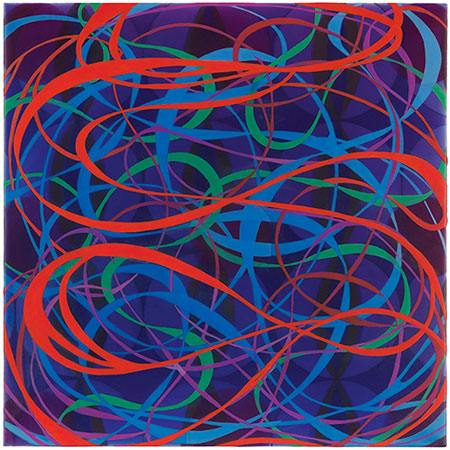

August Night, 2012, acrylic on wood panel, 12 x 12 in.

Which isn’t to say the work elides the metaphysical. It’s just that Simpson’s approach is absent of portent and pretension. A degree of sobriety, of practicality and routine, inflects the paintings, and can be gleaned in the manner in which countless scrims of paint have patiently been layered. (The waxy accumulations of pigment on the edges of each canvas also testify to Simpson’s painterly resolve.) But sobriety doesn’t define the art. Its rhythms are too hypnotic, the palette vivid-bordering-on-libidinous and the imagery palpably human in its heady embrace of “imperfection.” A Freudian could hold forth on the hard-won synthesis of id and super-ego—minus, that is, the ego’s supplications. The rest of us will marvel at the détente brought to the dialogue between chaos and order. That it’s barely a détente at all is what makes the pictures thrilling.

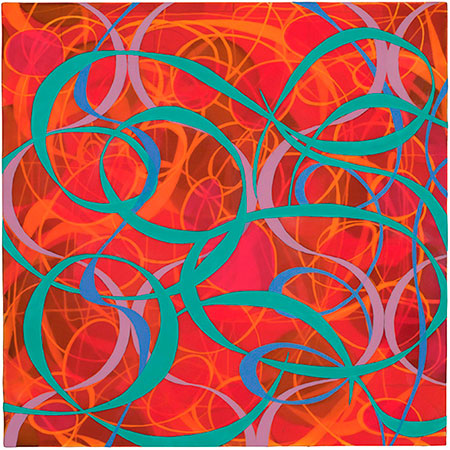

Lush Life, 2011, acrylic on wood panel, 12 x 12 in.

The ease with which the paintings announce themselves is an illusion, of course. (Simpson would be the first to admit as much.) That’s the point. Was it Fred Astaire who claimed “the trick” was in not letting the audience see you sweat? Much in the way Astaire defied the burdens of gravity and the limitations of the body, Simpson brings a profound calm to images that have been realized through a prolonged, sometimes exasperating and utterly necessary process. The work is nothing if it hasn’t encapsulated the sundry decisions that went into its making—in the application of a particular color, say, or the constant accounting for shifts in tempo and space. Simpson doesn’t advertise her labors. The painting is the thing—an entity with its own peculiar and independent life.

Simpson’s recent efforts are more of the same and a brand new thing—familiar turf that has been extended, made vibrant and, in the end, rendered altogether unfamiliar. Constitutionally incapable of coasting on her considerable expertise, Simpson has deepened the scope of her art even as she distills the particulars of its vocabulary. Paintings like Green Links, Seamless and the whiplash intricacies of Lush Life (all 2011) not only give a good name to the notion of continuity of vision, they give it body, truth and, yes, beauty. The latter is a rare and welcome entity, as recognizable (and undeniable) as it is impossible to define. That Simpson has embodied not a few of beauty’s many contradictions is ample reason to relish her hard-won and stunning achievement.

Mario Naves is an artist who lives and works in New York City. He teaches at Brooklyn College, Pratt Institute and Hofstra University. Naves’ collected writings can be found at the blog Too Much Art.